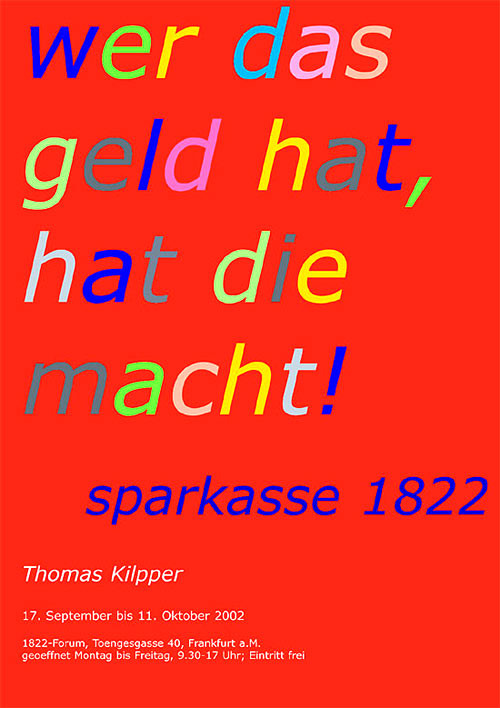

he, who has the money, has the power!

Forum of the Sparkasse 1882,

Frankfurt 2002

I was invited to do a show in September 2002 at the

Frankfurter Sparkasse (Savings Bank). For more than 120 years bees

served the bank as their logo. I planned to place a bee-hive in the

middle of the exhibition-space so that the bees can fly into the open,

collect the nectar and bring it – the ‘gold’ – to the bank. Public

assets turn private – as an equivalent to the dominant tendency, to

develop the public space according to private interests. I got technical

advise and support from the head of the Frankfurt

University-Bee-Institute.

The show should include a public hung

poster, a catalogue and a public discussion-meeting. because of my

research and critical view and statement about the bancs involvement in

the Third Reich I got univited and the show cancelled shortly before it

went on display.

From September 17 to October 11 2002 the exhibition space of the bank stayed empty.

(From the advertising of the Sparkassen-Finanzgruppe at Documenta 11)

No, its not.

In October 2001, I received an invitation to hold an exhibition within the framework of the ‘Jahresprogramm 2002 der Galerie 1822-Forum’ from 17.09. to 11.10.02 in the rooms Töngesgasse 40 of the Sparkasse 1822. It is clear to me from the beginning that I will develop a new work for it. An installation that will deal with the place – in this case the institution “1822”, i.e. a financial institution.

I therefore suggest that those responsible use material from the Sparkasse archive to critically shed light on the history of the bank, especially the period of Nazi fascism. This proposal is rejected. I do not get any insight into the archive with the documents from this time. This is justified by the “1822” with its responsibility for the “protection of customers and banking secrecy”.

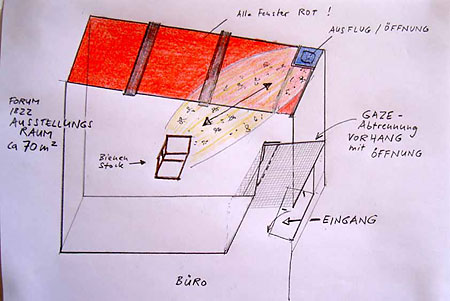

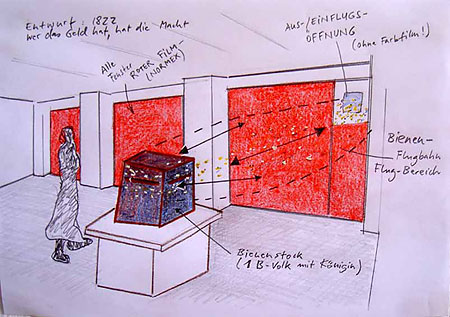

Even with my second proposal, I initially met with little approval: for over 160 years, the Sparkasse used bees and beehives as company logos and logos. Symbols for diligence and thrift. I would like to bring the bees back to this place as living beings. In the middle of the room a beehive is to be set up in such a way that the bees have the possibility of flying outside through a window opening.

Only the words of Professor Nikolaus Koeniger, the director of the institute for bee science (a daughter company of the “1822”), who kindly agrees to take over the list and support of the bees, can convince the responsible persons of the savings bank. From now on, it is planned to use red transparent film on the windows to bathe the entire room in red light and thus direct the bees on a trajectory to the window opening.

The possibility for the bees to fly outside, to collect the “gold” in the public space and to store it in the rooms of the Sparkasse… are metaphors that deliberately refer both to the history (and function) of the bank and to this year’s theme of the exhibition series, “Art and Public Space”. In this context, the bees are a kind of ambivalent symbol that can be perceived as both lovable and threatening.

Parallel to the practical preparations for the installation, I am working on the invitation card, poster, and catalogue that accompany this exhibition.

Even without being able to fall back on the Sparkasse’s archive, I try to form an impression of the bank’s earlier activities – especially during the period of Nazi fascism. I go to the city archives, obtain information from the Jewish Museum, the Fritz Bauer Institute, and read the “Chronicle of the Frankfurter Sparkasse” by Friedrich Lauf. The results of my research will be incorporated into the text in the catalogue that accompanies the exhibition.

The “1822” insists on the recognition and cultivation of its “proven traditions”, celebrates – not without pride – its 150th, 160th, 175th anniversaries – and includes the 12 years of Nazi fascism as silently as naturally. At the same time the company history in the Third Reich is described more or less from the perspective of the victim: “It remained for those responsible… there was nothing else left but to… for the sake of the survival of the Savings Bank.” (“Chronicle of the Frankfurter Sparkasse 1822”, p.185 by Friedrich Lauf)

Even before I can deepen this idea, I am stopped by the “1822”. On the contrary, I am now informed that my invitation to the exhibition as a whole may be revoked, that my person and my work have been “misjudged”.

I then formulate a compromise proposal: I renounce the planned events and promise to concentrate in my catalogue text on researching the history of the “1822” – the exhibition / installation is to be realized unchanged.

It will take almost another three weeks: on 31 July I will be informed by telephone that my exhibition will not be approved and that I have been uninvited. There is no written explanation, it simply means “we can’t do that”. A decision by the Board of Directors.

I was aware that my intention to take a critical look at the inviting institution could lead to certain tensions. However, in keeping with the exhibition conditions, I expected the Sparkasse to respect the freedom of artistic work.

That was obviously a misjudgement. Just as my hope was wrong that my contribution would be welcomed as an occasion for further discussion of these issues inside or outside the “1822”.

This experience reminds me of conflicts that had long been believed to have been overcome: there were always heated discussions between my father and myself on the subject of ‘fascism’. On the one hand I wanted to be able to love my father, but on the other hand I had to reject or even outlaw his actions and an important part of his person. The more intense our discussions about the time of fascism and the war became, the less I was able to understand him only as a “victim”. On the contrary. I had to see him more and more as a soldier, armed – on the side of the aggressors. It was disturbing to see my father in these conversations for a long time almost incapable of self-criticism, but with a tendency to justify himself.

Today there are attempts from various sides – not least by artists – to draw a line under the argument about ‘the dark chapter’ of German history and to free oneself from the ‘one-sided burden of guilt’ (Martin Walser). But in a time in which it is virtually considered necessary to speak of the suffering and victims of the Germans in and after the Second World War (as in Günter Grass’s novella “Im Krebsgang”) – in a time characterized by the attempted “transformation of the German culture of remembrance: from perpetrator society to victim society” (Neue Zürcher Zeitung, April 3, 2002) – I consider it indispensable to research and thematize further historical facts and insights. Findings that not only deepen our awareness of history but can also be helpful in shaping our present emancipatively and progressively.

After being denied access to the archive, it became one of my goals to use my work to bring into play the idea and the request to make the archives (from the Nazi era) of the German “traditional” companies – and thus also that of the Sparkasse “1822” – accessible to independent historians.

It is regrettable that the Board of Management of Frankfurter Sparkasse in 1822 is attempting to prevent this conflict and testifies to an extraordinary short-sightedness in dealing with its own history. Moreover, the behaviour of the “1822” contradicts any claim to a democratic and critical discourse.

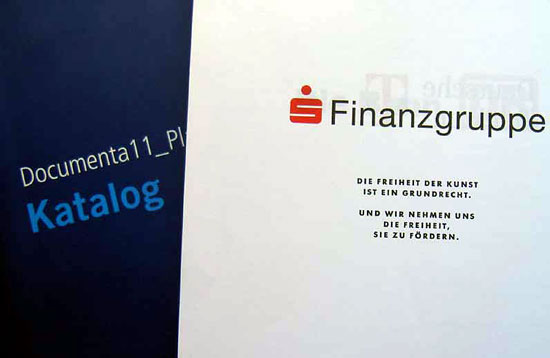

The fact that the association organ of Frankfurter Sparkasse, the Sparkassen-Finanzgruppe, promotes Documenta11 with the melodious slogan – “THE FREEDOM OF ART IS A BASIC RIGHT” – can only be read bitterly ironically after this incident.

Thomas Kilpper – London, August 2002

PS: Further distribution expressly welcome