Planning don’t look backThomas Kilpper was confronted with a vast space and an enormous part of history: Camp King, in the vicinity of Frankfurt/Main, was used after 1945 by the US secret service for interrogations of significant Nazi militaries. Here it was decided who would go to court and who would be integrated into American intelligence services. During the war Camp King had been the central prison of the NS Luftwaffe (German air force) where all shot down pilots of the allied forces were interrogated.

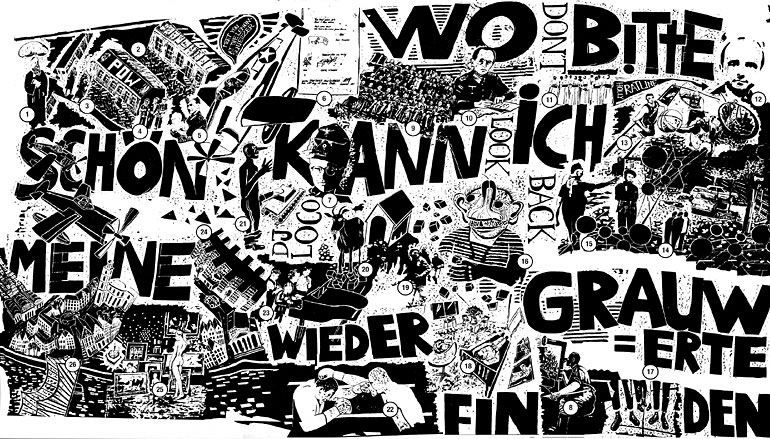

Thomas Kilpper chose to cut open the parquetry floor of the former basketball field and transform it into a large-scale printing block. The result was a huge woodcut that would newly occupy a place that had gone through many transformations – empty after the military use the building was torn down and rebuilt for public use – with the purpose to examine the location’s history and intervene in its transformation process. The images from the woodcut were printed on modern textiles and digital advertising posters.

Patrick Heide

(www.patrickheide.com)

It consists of a woodcut of gigantic dimensions that depicts various scenes, which refer not only to the history of the site but which also reflect the artist’s own history.

Camp King was initially a Reichssiedlungshof for the National Socialists during the Third Reich, then later a Luftwaffe transit camp for captured Allied pilots, and at the end of the Second World War, it was taken over by US Army and the CIA. Kilpper was marked by the Cold War period, as well as by the political developments of the Seventies and Eighties and he tackles his father’s past as a member of the German Armed Forces. In various of the images there are references to himself. In this way a common history can find an echo within a personal one. The artist reflects his own biography against this background.

Since 1993 the town of Oberursel has been planning a civilian re-modelling of the site. However, to this day, the neglect of the former military area continues to generate a surreal, morbid atmosphere.

The artist’s initial selection of this location was a consequence neither of content nor of aesthetically based concerns, but rather born first and foremost of practical reasons. For the realisation of an oversize woodcut, Kilpper was seeking a building condemned for demolition and containing a parquet floor, and he found in the oak flooring of the unoccupied gymnasium within Camp King the ideal printing plate. The choice of site led to research into locality, and a content-based analysis, portrayed by the artist in a narrative sequence of individual scenes on the wooden floor. He then took prints of separate images on paper, wallpaper and material and hung them on lines strung across the room. In this way, the visitor could experience the positive and negative versions of an image simultaneously, and, so to speak, walk through the space while reading its history. This work of Kilpper’s would be inconceivable without the specificity of the site. It was realised in situ. For this reason, it was not at first possible to imagine preserving the piece independently from the building. However, the work has stirred in the population an awareness of its own history and so there is now a plan from the Town Council to cast the piece in cement and to install it permanently as a “Streetball” court. With this in mind, the floor has already been sawn up into individual sections and preserved. Now the hope is that the plan can also be financed and subsequently realised (meanwhile realised and inaugurated in 2003), thus leaving a lasting impression both of the site and of the human destinies dependent upon it.

Angelika Nollert

Portikus, Frankfurt/Main 1999

Translated by Josephine Pryde

Felix Philipp Ingold

History, they say, leaves its mark. This commonplace phrase disguises what actually occurs – people leave their mark on history. Undoubtedly, the one state cannot compensate for the other. A tension remains, an insoluble dialectic through whose dynamic it becomes unclear whether the individual has a particular position in relation to conditions, or whether the conditions – the famous class, political and social conditions – have been allocated to the individual. And then whatever you have ready to serve by and large as an explanation for your own situation is always only going to be a story, even when it is grandly described as a history – a story interpreted in a particular sense, however much the explanation may also intend to be objective.

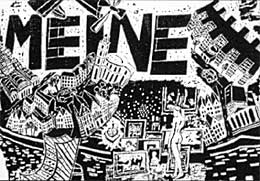

Thomas Kilpper’s woodcut in the former basketball court of a site steeped in history in Oberursel is located both concretely and metaphorically within the field of these problematics. With this work, his attempt to occupy a position in the present is born out of the conviction that this will not be possible without confronting the past. What Kilpper has cut and shaped into the parquet floor, across a surface area approaching 300 square meters, has to do with the history of the place and with the destinies of the people who went about their business there, as well as with his own biography.

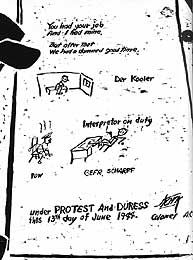

The series of images begins with Kilpper’s great grandfather’s time as a missionary in South East Asia but reaches its first main focus during the period of World War II. The site was an assembly camp for captured pilots of the Allied Air Forces. Here, they were interned and interrogated. The reigning atmosphere of the period was tied to the values of the so-called soldier’s code of honour. This led to the expression of respect for the enemy officer, also utilised by Kilpper: “You had your job and I had mine.”

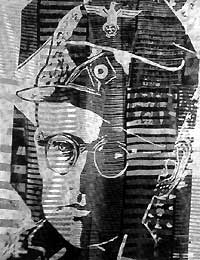

At the end of the war the site was taken over by US Forces and was used mainly for secret service purposes. The enemy was no longer the German troops but instead the communist Soviet Union. There was now partial collaboration with the former National Socialist enemy. With “Operation Paperclip” the US Americans tried to deploy German scientists and sections of the political elite for their own ends, thereby divesting them of accountability for their work under the National Socialist State. In the course of these actions, Klaus Barbie was pretty much able to slip away from Oberursel to Bolivia. And Reinhard Gehlen, former Chief of the National Socialist Secret Service “Fremde Heere Ost” (Foreign Army Eastern Division) founded the so-called “Organisation Gehlen” in Oberursel, the forerunner to the subsequent Federal Secret Service (Bundes-Nachrichten-Dienst, BND). The overlapping of personnel discernible within these two examples, and the power relations that endured across ideological and political divides are significant for Kilpper’s work. He follows them through right up to the present time. The image of the execution of a member of the Vietcong (US soldiers were trained in anti-guerilla warfare at Oberursel at the time of the Vietnam War) and the image of the kidnapping of Hanns-Martin Schleyer are examples of this. (Schleyer, as a former member of the SS with a position of leadership in Eastern Europe, and later as President of the federation of German employers’ association was a practitioner at high political level of the above mentioned overlapping in the deployment of personnel.) And this is where Kilpper’s own biography comes into play. It is marked by his father’s confrontation with the past as a member of the German Armed Forces (Wehrmacht) and also by the political conflicts of the Seventies and Eighties in the spheres of left wing radicality.

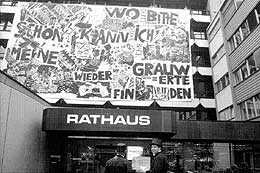

Through the subjects of the pictures, which are not presented according to either a rigorous thematic or to a chronology, Kilpper sets in motion the question “Where, pray, might I get my grey tones back again?” This question is aimed at the loss of differentiation within political confrontation and treatments of history. It is not for nothing that Kilpper uses as his models photos that are widely known and often reproduced by the media. Through these pictures he can on the one hand make the political intention of this work more accessible and on the other hand, he also demonstrates an approach that is only allegedly simple with regard to the historical developments in which we are situated. For it is not as if the question simply swings between the poles of black and white, or good and evil. To understand it requires much more than the simplistic signals transmitted via pedagogical or other mediation.

Kilpper turns the cliché of bearing-the-mark-of-history around and uses it graphically, in the printing sense. Through prolonged and heavy-duty work, he has chiselled a history into the floor. He has made his mark on the history-bearing images through the act of his physical labour. He has appropriated them in the fullest sense of the word. Through working on his woodcut, he has transformed the feeling of being overpowered by history into the energy of the overpowering itself. The fact that in the process, he destroys the parquet floor, cutting it up with chisel and chainsaw is not the least important aspect of the work. For the flooring, at one time functional and in use for basketball games, can be taken as a symbol of an unalterable history whose end has been written – and whose authority has been stolen by Kilpper. His way of working can also be compared to hip hop sampling. Just as there, Afro-American musicians utilise elements taken from pop music history stamped “white” in order to realise a tradition of their own, so Kilpper utilises samples from the “official” history in confrontation with his own, with the view to making them his own, too.

He has used form to solve the problem of a mere reversal. As it stands, the enormous woodcut is at best half of the work. You could say that it simply becomes the tool towards a further step. For the whole series of images can be seen in their mirror versions. The woodcut is therefore a negative. Prints can be taken from it that show the images the right way round. It is the printing plate for the pictures that Kilpper prints on to various materials, materials whose origin and structure play an important role in their use. The curtains and wallpapers stand for the border between private and public space, whilst advertising posters and flag fabrics bring with them an assortment of influences through their symbols and invitations to identification. For the most part, Kilpper hangs the prints up on thin ropes across the space of the former sports hall and makes the positives confront their own negatives, cut into the floor beneath them. Once again, the viewer is caught in the middle, where it lies with him or with her to confront both the depicted images and the associations that Kilpper draws, and to get the missing grey tones back.

Martin Pesch is a music and art critic (for, amongst others, Frieze, Spex and Kunstforum International), Frankfurt/Main.

Translated by Josephine Pryde